Half a billion years ago, the oldest rocks of today’s city, Fordham Gneiss, lay south of the equator in a shallow ocean just off an early continent. Sea creatures lived and died there, leaving shells behind that collected on the ocean floor, slowly forming beds of limestone. Mud and more sediments, together with volcanic ash from a nearby string of volcanic islands, compressed over time to form a layer of shale.

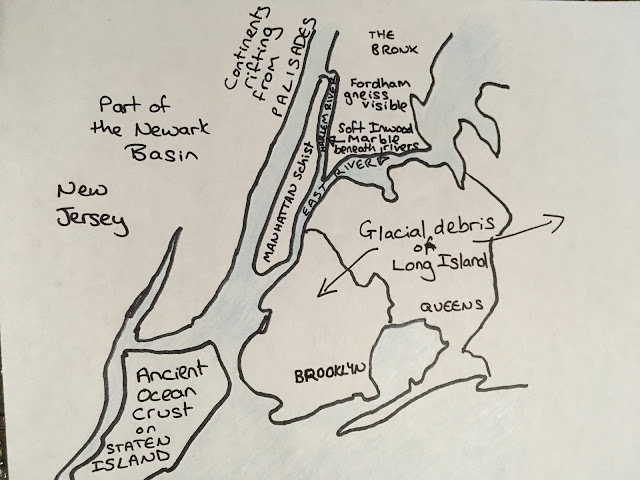

The volcanic islands were a sign that the continents were on the move. In an almighty slow-motion crash, the volcanic islands collided with NYC's early continent. Land crumpled, sending up a mountain range as high as the Himalayas that stretched from Newfoundland to Alabama. The beds of limestone and shale were buried and inter-folded together with the ancient gneiss, where the overlying weight of a continent triggered their metamorphosis into different types of rock. Meanwhile part of the ocean crust between the volcanic islands and continent got caught up in the collision, and is preserved still in Staten Island.

The collision was just the start of a continental pile-up. Eventually, about 300 million years ago, most the land on Earth was contained by Euramerica in the north and Gondwana in the south. When these two collided, the supercontinent Pangaea was created. New York City’s place in this supercontinent? Not near an ocean but in the middle, where it was bound to the future west Africa.

|

| Rat Rock: Hunt for folds and glacial grooves in the schist |

Through it all, the rocks that started out as limestone and shale remained intertwined with the ancient rock. The former limestone, transformed into soft Inwood marble, now lies under the Harlem and East Rivers. The former shale, compressed by mountain ranges into tough Manhattan schist, is now able to withstand the weight of Manhattan’s skyscrapers. The schist runs down the length of Manhattan, dipping briefly deeper underground south of Midtown and rising back at the southern tip of the island ready to support the skyscrapers of the Financial District. The valley between is filled in by glacier debris.

|

| Dragged there by a glacier |

Long Island marks the southern boundary of the past glaciers, indeed was largely formed by glacier debris because the glaciers advanced at roughly the same pace they melted, bringing a steady supply of rocks.

Take a walk around Central Park and you won’t be able to miss the exposed schist with its glacial etchings. You’ll know it by the glittery flakes of mica, a mineral that forms in rocks with a long history, deep below the ground over millions of years.

|

| Rough sketch of NYC area |

Further reading:

History of New York Geology, New York Nature

Geology of New York: A simplified account, Y.W. Isachsen, E. Landing, J.M. Lauber, L.V. Rickard, and W.B.

Rogers, editors, New York State Museum

Fantastic, Kate. I've read this story a dozen times and haven't been able to convey it this clearly to others or to me! One starts with layers of sand in an ocean and ends with the hard bedrock of Manhattan schist - every step in between is as fascinating as the next.

ReplyDeleteInteresting article, Kate. I will have to pay more attention to rocks in Central Park or Palisades more.

ReplyDelete